This article is part of a partnership between The Jersey Bee and Next City to explore racism in Essex County, New Jersey and solutions to build a more just and equitable county and state.

In Montclair’s Ward 3 there is a small farm with great community value.

During the summer, Montclair Community Farms transforms its less than 10,000 square foot lot into a space for everyone: a gardening education program for children, a job training site for teens, and a pop-up farmers market for Essex County residents.

“People really like it here,” said Lana Mustafa, executive director of Montclair Community Farms. “It’s really evolved into a really beautiful, productive, community-oriented place.”

On a breezy afternoon in early June, bunches of lettuce, bok choy, parsley and garlic begin to sprout and ripen. Some are even ready to harvest. Mustafa and her team are preparing inventory for their Monday farmers market, where dozens of shoppers use their SNAP or WIC benefits to buy fresh produce.

READ: How to Apply for Food Stamps and Assistance in New Jersey

But Mustafa said serving the people of Essex County isn’t easy when the government doesn’t see urban farming as a viable solution to bringing fresh, affordable food to food-insecure communities.

To do so, the state must confront the complex history of agriculture and combine it with long-term municipal investments — steps some say New Jersey has yet to take.

“We need the state of New Jersey to urbanize. [agriculture] “I’m serious,” said Mustafa.

Mustafa said bureaucracy has repeatedly hampered her small farm’s ability to serve her community. Because she doesn’t have at least five acres, her application to the federal Senior Farmers Market Nutrition Program—which would allow her to accept food stamps from low-income seniors—was denied four times. Only after extensive lobbying with other community groups did the USDA approve her application in 2023.

The high cost of the permit (up to $5,000 per year) forced her to end her composting program this spring.

“What happens to all this food waste when we can’t take it anymore? It has to go back to the landfill,” said Mustafa, whose farm collects more than 8,000 pounds of food waste a year.

It’s no coincidence that urban farms located in and around Essex County’s seven food deserts receive little to no support from the city, said Emilio Panasci, co-founder and executive director of the Urban Farming Cooperative.

READ: How Essex County is Facing Food Shortages (and How You Can Help)

“Consumer access to food reflects our patterns of segregation in this country, and it is a political choice as well as an economic one,” Panasci said. “It is no coincidence that, aside from a few struggling small farms and pop-up markets in Newark’s South Ward, there are few or no fresh, high-quality food options — and those options come at a premium — in our neighboring Maplewood or South Orange.”

A photo of Montclair Community Farms’ garden beds, shed and community gathering area. Lana Mustafa says her farmers markets have grown from serving ten people to hundreds of residents in federal food assistance programs in recent years. Photo by Kimberly Izar

Discrimination in agriculture

While food farming may have its roots in Indigenous and Black farming, it was white farmers in New Jersey who benefited most from a slave-based agricultural economy.

In the 1700s and 1800s, farmers in the Garden State relied on slaves to herd and butcher livestock, plant crops, maintain pastures, and build their farms. Even after slavery was abolished in New Jersey in 1866, white farmers created their own form of sharecropping called “cottaging,” where formerly enslaved blacks would provide labor in exchange for housing and crops.

In her book Farming while black, Leah Penniman details what happened next for black farmers after Jim Crow and the passage of civil rights legislation.

Penniman wrote of the rise of black and Latinx farmers reviving agricultural traditions in the 1960s and 1970s: “Urban farmers of color cleared debris, planted trees, made vegetable beds, and built structures for community gatherings.”

Still, the legacy of discrimination lingers. A 2022 report from Rutgers University found that urban farms in New Jersey tend to be concentrated in areas with higher SNAP participation rates, where residents are more likely to be Black or Latino. And in a county where whites make up less than a third of the population, they own three-quarters of all urban farms in Essex County, according to the 2022 U.S. Census of Agriculture.

Fallon Davis, president of the Black and Brown, Indigenous, Immigrant Farmers Union (BIFU), said these inequalities are “systemic by design”.

“We have to understand that the system was never designed for black and brown people to live this long. It was never designed for us to thrive, to survive, to have families, and to be these beautiful creatures of the land.”

They explain that the lack of support for urban farmers primarily targets black neighborhoods in Essex County and exacerbates racial segregation.

“New Jersey has not prioritized urban agriculture, which would protect and feed black people,” they said.

Agriculture without water on borrowed land

A few miles from Montclair Community Farms, Keven Porter’s farm in Newark faces a host of challenges typical of urban farmers. For starters, he still lacks basic agricultural infrastructure — like running water.

More than a decade after starting Rabbit Hole Farm, Porter is still struggling to get a reliable water supply from the city of Newark. For years, he has had to ask neighbors or the fire department for water.

“They don’t know that we are a resource,” said Porter, a black farmer and Newark resident.

Porter and his partner co-founded Rabbit Hole Farm in 2013 through Newark’s Adopt-A-Lot program. Today, Rabbit Hole Farm is a 6,000-square-foot community center in Newark’s South Ward that offers herbal education, wellness programs, and cooking classes to Newark residents, where more than half of public school students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch.

Porter’s farm faces another common challenge: He doesn’t own his farmland. Through Newark’s Adopt-A-Lot program, residents can use vacant city lots but don’t own them, no matter how long they’ve tended them.

BIFU’s Fallon Davis also has a farm in Newark, run by their youth education nonprofit STEAM URBAN. They say Adopt-A-Lot is “a flawed system because [the city] can take it whenever they want.”

Both farmers are working with the Public Land Trust to find out how they can purchase their land in Newark.

“If we figure out how to help people own land, if we teach people how to grow their own food, if we teach people how to advocate for themselves, that will change our communities on its own, and they don’t want that,” Davis said.

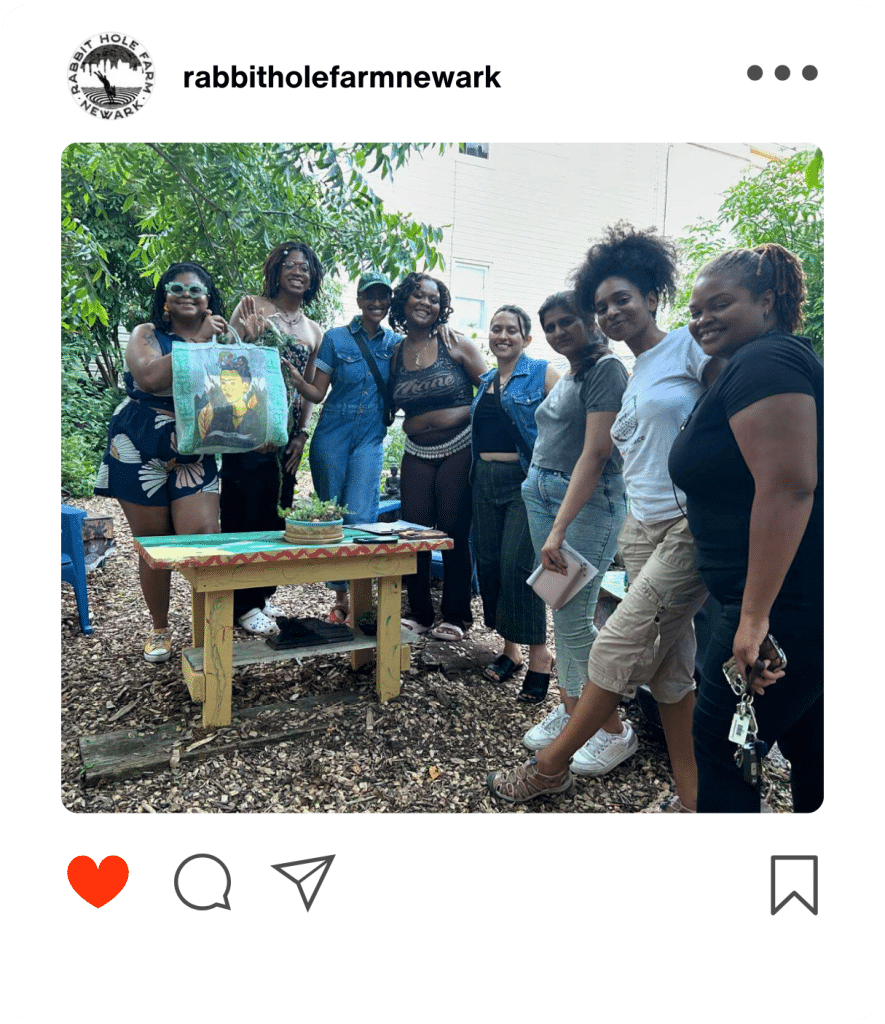

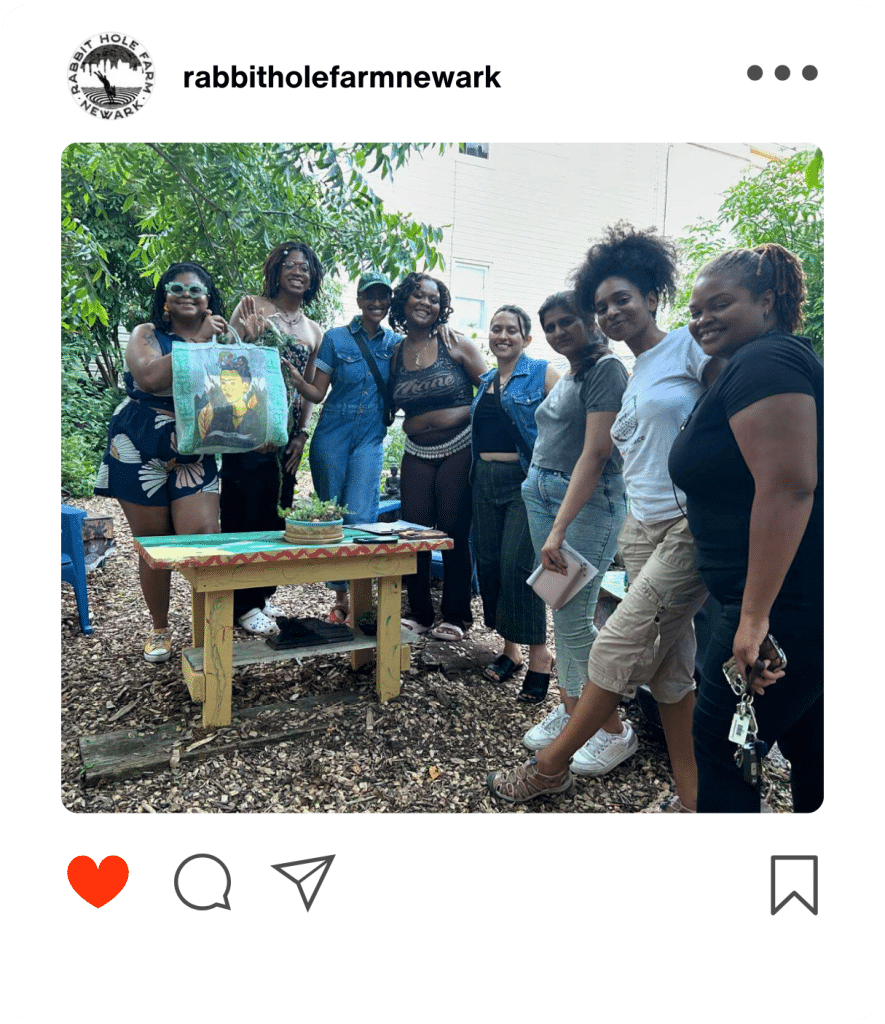

Herbalist Yaquana Williams hosted a Juneteenth plant discovery class at Rabbit Hole Farm in June 2024. Photo from Rabbit Hole Farm’s Instagram.

Solutions focused on long-term

Long-term solutions that allow for local food growing and markets in urban environments are key, says Panasci of the Urban Farming Cooperative.

“Our zoning here is different. Our density is different. When you combine that with the fact that we lack a cohesive urban agriculture policy at the local level… it’s very difficult for a farmer or a farmers market to maintain land over time and… build infrastructure on it,” Panasci said.

On Fridays, Panasci and his team prepare farm boxes filled with kale, endive, mushrooms, honey and eggs. His organization sources inventory from more than 30 growers across the state before the group distributes the boxes to schools, food pantries, hospitals and senior centers with limited access to fresh food.

Urban Farming Cooperative staff prepare farm boxes for families on a June afternoon in 2024. Photo by Nikki VIllafane

Panasci stressed that city support is crucial for urban farms, which are particularly vulnerable to gentrification and displacement by developers.

“Farming in general is hard, but urban farming without necessarily having a real city system for it… it’s almost set up not to work. [and] to really weaken you,” says Panasci.

Urban Farming Cooperative distribution bags are loaded onto a pickup truck at their warehouse in Irvington, NJ in June 2024. Photo by Nikki VIllafane

Over the past few years, several bills have been introduced aimed at formalizing urban farming policies and sustaining the industry.

In January 2024, Councilwoman Annette Quijano reintroduced a bill to establish an urban agriculture pilot program for emerging urban farms. Senator Teresa Ruiz and Senator Nellie Pou also reintroduced a bill to establish an urban agriculture grant and loan program. Neither bill moved out of committee for further consideration.

Jeanine Cava, executive director of the NJ Food Democracy Collaborative, points to the Massachusetts Healthy Food Incentive Program (HIP) as a potential model for what could happen in New Jersey. This state-funded program reimburses SNAP users when they buy food from eligible HIP vendors.

“Currently, we don’t have state funding specifically for those kinds of incentives that encourage people to buy locally produced food,” she said of the lack of fixed funding.

BIFU’s Davis emphasized that Black and brown farmers need to be at the center of any urban farming solution. BIFU’s 40-member statewide group plans to release its policy resolutions later this summer, which include recommendations on land ownership and state funding for BIPOC farmers.

“We also need to give [politicians] Some of the language in our request… the community needs to do some work,” they said. “If you want your community to change, you have to support your community.”

Find out more

Learn more about upcoming programs and events at Montclair Community Farms and Rabbit Hole Farm.

You can also get involved with Urban Agriculture Cooperative, Black & Brown, Indigenous, Immigrant Farmers United and NJ Food Democracy Collaborative through programming and advocacy opportunities.