Hunger and food insecurity exist in every community in the United States. About 12.8 percent of U.S. households experienced food insecurity in 2022.

That’s 17 million households experiencing food insecurity in a country that throws away more food than any other in the world—120 billion pounds per yearequivalent to nearly 40 percent of the total food produced in the United States. That’s 325 pounds of food wasted per person.

In other words, no one in the United States should go hungry. There is plenty of food to share. It’s just a matter of getting the food to the hungry before it goes to the landfill to rot and, in the process, produces a huge amount of methane gas that contributes to climate change. estimate eight percent of global carbon emissions.

While we all wait (not holding our breath) for the government to act, a network of community activists has sprung up in small towns and big cities to help get food to those who need it most. Every community has different needs and there is no one-size-fits-all solution, which makes this highly personalized approach more effective than many of the more generic, large-scale government-funded options available today.

Nancy Walker-Keay of Walker-Keay Farms in Eliot, Maine, regularly brings in meals and fresh produce from the farm. Photo via Seacoast Fridge.

Seacoast Fridge Partners with Local Farms and Food Trucks

“A colleague told me about the rise of community refrigerators that provide free food to anyone who needs it, no questions asked,” Whitney Blethen recalls of the early months of the pandemic, when it became increasingly clear that people were hungry and resources were scarce. “I work for a nonprofit that fights childhood hunger and I’m married to a chef, so it felt like a natural progression.”

Along with Katie Guay and Dave Vargas, Blethen founded Seacoast Refrigerator in Kittery, Maine in 2021.

“We found that Good Samaritan Food Donation Act “It protects the people who operate the refrigerators for free, making us feel like there is no risk and only benefit,” said Blethen.

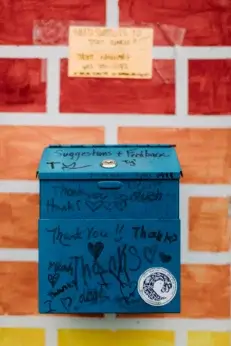

The suggestion box at Seacoast Fridge allows volunteers to hear directly from community members. Photo by Alayna Hogan.

They contacted the local rotary club so they could “tap” their general liability insurance, which covers a wide range of potential injuries or accidents that could occur while picking up or delivering food. Ultimately, they partnered with Red’s Good Feelingsa free mobile food truck and non-profit based in Portsmouth, NH, aligned with their mission and expanded their reach.

“It was a game changer,” Blethen said. “They had a network of farms, andSince we all have experience with food safety and liability, we started labeling food from the beginning with ingredients and expiration dates to prevent any problems.”

At first, one of their fridges would be emptied every 72 hours. Now, they plan for 24 fridges this year, with current rotations of up to four times a day per fridge. Their mission has grown along with their operations, and they now have 150 volunteers. They’ve also started food rescue programs with farms and restaurants, where “some farms allow CSA members to add $5 to their order. They use that to fund additional deliveries to us.”

In addition to fresh food, Seacoast also offers seasonal food items, from sunscreen and tick spray to socks and gloves.

“We also work with the local Land Trust and they have kids tend the garden,” Blethen says. “All the food is then donated to the fridge or pantry. It’s great for everyone, including the kids.”

To learn more, donate, or find a free fridge in Maine or New Hampshire, follow Seacoast on Instagram at @seacoastfridge.

Local artist Mariah Cooper paints the first refrigerator for Sweet Tooth Community Fridge. Photo by Monica Owczarski.

Sweet Tooth Community Fridge Takes Advantage of Tax Credits to Pay Farmers

“In Iowa, our legislature is hostile to the poor,” said Monica Owczarski. “With the city not doing enough to combat poverty and our own situation, we knew we had to do something.”

Starting in 2016, Owczarski ran a pop-up food pantry near her urban farm, Sweet Tooth Farm, in Des Moines. Once licensed, she began accepting food stamps. During the pandemic, Owczarski saw demand increase dramatically and official support decline. Then, in 2021, the city change the rules of agriculture and Owczarski went from producing just over an acre to producing about three city blocks.

Monica Owczarski and Kennady Lilly of Sweet Tooth Community Fridge, farming. Photo by Monica Owczarski.

“We were down to a tenth of our space, which meant we couldn’t produce enough for our restaurant and CSA customers on a weekly basis,” Owczarski said. “Then a soup kitchen near us closed.” That was the last straw for Owczarski.

She reached out to other nonprofits, farmers, and food organizations and started giving out free food to anyone who wanted a refrigerator, no questions asked. It was the first refrigerator in the state. And it actually helped Owczarski pay the bills after her CSA and farm model went haywire.

“The [Farm to Food Donation Tax Credit] “The program pays farmers for the food they donate,” she explained, adding that they also receive donations from restaurants, caterers and others who have excess food that would otherwise go to landfill.

Currently, the network has 16 refrigerators but is completely decentralized.

“In the last 30 days alone, we’ve saved 200,000 pounds of food that would have otherwise been thrown away,” Owczarski said. “Every neighborhood’s needs are different, some don’t need pork for religious reasons and others need more of one thing or another just because of the community they serve.”

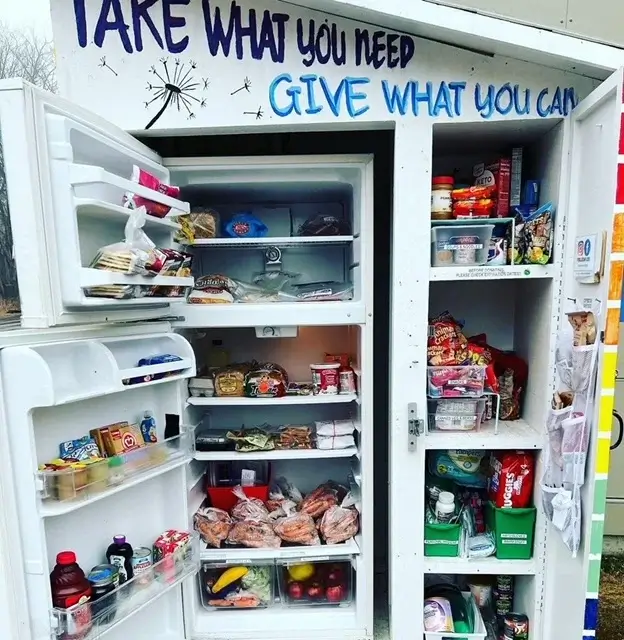

Inside the Sweet Tooth community fridge. Photo by Monica Owczarski.

The biggest challenge is climate, Owczarski said.

“We had to figure out how to prevent the refrigerator from shorting out on days when the temperature dropped to -40 degrees,” Owczarski said. “We insulated the refrigerator, built shelters, and even had fire-safe infrared heaters that turned on when the temperature dropped below a certain threshold.”

To learn more, donate, and find fridges around Des Moines, follow @sweetthoothfarmdscm on Instagram.

Free Food Fridge Aims at Nonprofit World

Jammella Anderson was founded Albany Free Food Fridge during the pandemic.

Founder Jammella Anderson with a community fridge. Photo by Yiyi Mendoza/Free Food Fridge Albany.

“Access to fresh food and produce has been an issue for years in Albany and many other places due to systemic racism and discrimination,” Anderson said. “The pandemic has made things worse for everyone, and people who were already struggling to get by but were living on the edge of their incomes suddenly found themselves without options during the pandemic.”

If someone makes just $10 above the threshold for SNAP or other income-based benefits, they’re out of luck, they explain. That means “a lot of people are going to go hungry,” Anderson says.

Food distribution in Albany. Photo by Yiyi Mendoza/Free Food Fridge Albany.

Seeing what was happening in Albany, the midwife and part-time yoga instructor took action, calling out her Instagram followers and winning a free refrigerator from Lowe’s and a location to put her first refrigerator on Elm Street in Albany.

The free food fridge has grown significantly since 2020 and will have 21 fridges around Albany by the end of the summer. Donations come from individuals and farmers. Some are regular, some are one-time, some are in the form of food and some are in the form of money.

“Our next phase is to officially become a nonprofit since we are volunteer-run and create a mobile grocery store that can travel around Albany, go to all of our refrigerator locations, and act as a pop-up store at farmers markets and food justice organizations,” Anderson said.

Jammella Anderson. Photo by Yiyi Mendoza/Free Food Fridge Albany.

They are also trying to change the way we talk about food access.

“You can’t say a hungry person looks like this or underserved communities look like that,” Anderson said. “We need to change that conversation because, just like there’s no one solution to hunger, there’s no one type of hungry person or underserved community.”

To learn more, donate, and find a refrigerator in Albany, follow Free Food Fridge Albany on Instagram.

RVA Community Fridge for Kids Gathers on Social Media

“I grew up with community refrigerators in New Orleans, but that’s not really done here,” he said. RVA Community Refrigerator founder Taylor Scott. “And I saw SNAP benefits being cut in Richmond, and all these historically segregated areas not having access to grocery stores or other resources, and I knew I had to do something.”

Taylor Scott at Matchbox Mutual Aid picks up fresh local produce from a farm partner to distribute to the RVA Community Fridge. Photo by Brittany Chappell.

The project started small, when an overgrowth of tomatoes threatened to take over her apartment during the pandemic. She sought out a community fridge to donate her bounty, hoping her fresh produce could help provide fresh produce to underserved areas.

But Scott couldn’t find any community fridges. She contacted a local bakery in Church Hill, and they agreed to rent one. It was installed in January 2021. “As soon as we filled it, it was empty,” Scott said. “Now we have 14 fridges, and the whole community is involved. We have over 300 volunteers who help us buy food and run it, not to mention the people who just leave things in the fridge.”

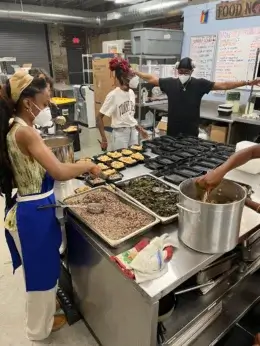

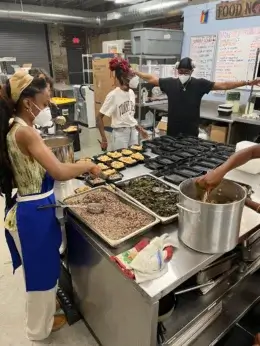

Taylor and community members at Matchbox Mutual Aid Community Cooking Day prepare meals to stock the RVA community fridge. Photo by Harmony.

Scott communicates with volunteers, farms, caterers and chefs who donate food that would otherwise be landfilled through a communication platform. Discord and the social media groups she created. Their refrigerators and pantries filled with household items were sometimes emptied in as little as 30 minutes.

“I love seeing these refrigerators bring our community together,” Scott said. “Some neighborhoods are in dire straits for food, and raising awareness among Richmonders who otherwise wouldn’t know what’s going on in these neighborhoods, while also feeding people and combating food waste, is amazing.”

Scott said the group is in the process of applying to become an official nonprofit. To learn more, donate, and find a fridge, follow RVA Community Fridges on Instagram.

RVA Community Fridge #14 Matchbox Fridge. Photo by Taylor Scott